The dilemma of reality television and what it means for the future of archaeology

By Jerry D. Spangler

In years gone by, when I used to teach archaeology methods, I used to give the students an assignment to watch their choice of the Indiana Jones movies and develop a research design for his “investigations” that would pass muster in the modern world. It was a critical thinking exercise intended to be fun, and we did have a lot of laughs.

But it seems it is no laughing matter in today’s world of reality television where vast audiences of millions tune in every week for the thrill of watching a protagonist discover exciting artifacts.

The unbridled quest for artifacts is unquestionably anathema to modern archaeologists, who by and large hold themselves to rigorous research standards. But the Indiana Jones mentality is thriving in the real world thanks to reality shows like Diggers, American Diggers, Dig Wars, Time Team America, and probably a few more I haven’t heard about.

I admit I was flummoxed and even afflicted with vapors of righteous indignation when I learned some time ago that National Geographic Society had sponsored the television reality series Diggers – which in my mind was little more than glorified looting. Surely something so ethically reprehensible would not survive the public brouhaha.

Not only has it survived but it is bigger than ever. According to Society for American Archaeology President Jeffrey H. Altschul, 30.9 million viewers tuned in to watch Diggers over a five month period in 2014 –ratings gold for any cable channel. And that does not count the millions more who watched the other reality shows.

“Why such huge audiences?” Altschul writes in the March message to SAA members. “Because the public really likes and is interested in archaeology and history.”

Furthermore, he adds, “Don’t we have an obligation to the people who watch reality TV, as well as to the viewers of NOVA? I think we do. But we also have an obligation to ensure that these shows portray archaeology in a way that meets our standards of ethical conduct and scientific practice.”

I couldn’t agree more. But as a profession, we are late to this party and we forgot to bring wine.

The public demands to know about archaeology, but what do we give them? The same thing over and over. Most places have a “Prehistory Week” or a “Prehistory Month” with maybe some site tours or museum exhibits, there might be lectures here and there, and once in a while our issues get good coverage in the local media. PBS and other educational documentary outlets have done a great job on archaeological topics.

But the reality is these traditional means of communication reach an infinitesimally small portion of the public who actually cares about history and archaeology. And we certainly aren’t reaching the millions who tune in to reality television.

The appetite for archaeological knowledge is massive, but our profession – yes, I am directing this at my archaeologist friends and government officials whose job it is to “protect” archaeology – have done painfully little to satisfy that public hunger to know what it is we do, why we do it, and why it is important.

And others have now stepped into the void to serve up a dish we find so unpalatable to our ethical sensibilities. It’s not just reality television, but digital and social media. You can now Google just about any moderately well-known archaeological site in the United States and come up with blogs about it, directions to it, even entire web pages devoted to it. To say the messages are “imaginative” is to put it mildly.

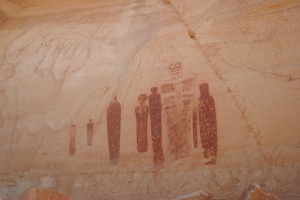

We recently took our photographer friend Jonathan Bailey to a site we assumed was off the radar because to get to it you had to cross private lands posted no trespassing (yes, we had permission). I thought I was sharing something that few ever get to see. The following week, he sends me links to a recent blog site he had found that has detailed photographs of the site and directions on how to find it – all without a single mention that visitation involves trespassing and not a single word about the proper behavior expected when visiting such a site.

Any proactive message we might have hoped for this site had been hijacked by the “wow” crowd.

The consequences of our failure to communicate could have dire consequences for the resources we are all passionate about, Altschul warns.

“As archaeologists, we have an ethical obligation to tell the public what we have learned (SAA Ethical Principle No. 4),” he writes. “If that is not enough, we have our own self-interest. Most of us, whether in academia or CRM, are supported either directly by public funding or by laws and regulations. Unless we communicate why what we do is in the public interest, we run the real risk of having these funds shut off and the regulations protecting archaeological resources lifted or eviscerated.”

And that reality would really bite.

Jerry D. Spangler is executive director of the Colorado Plateau Archaeological Alliance. He can be reached directly at jerry_cpaa@comcast.net.

The entire March edition of the SAA Record is a must-read examination of the ethical dilemmas inherent in reality television. It can be found at http://onlinedigeditions.com/publication/?i=249469 or by going to the Society for American Archaeology website.